Retinoblastoma: the discovery of a darkling gene

Someday people might be able to design a treatment by making a drug, that, instead of inhibiting the “bad” pathway, mimics what the “good” protein is doing.

Retinoblastoma, an eye cancer that only afflicts children under the age of four – is as rare as it is tragic. It occurs in one of 20,000 births and is the most common primary malignant intraocular cancer in children. For a long time, people have been trying to find out the cause and treatment of retinoblastoma, and during those glorious days, scientists revealed the first tumor suppressive gene.

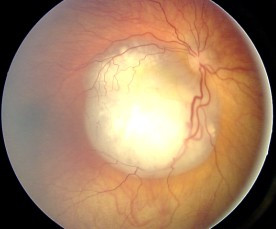

Retinoblastoma in right eye(aravind.org)

The deadly eye tumor

Fighting with retinoblastoma is a horrible experience. Some children lost their vision, some even lost their lives. Even if a child survives from retinoblastoma, he may have the hereditary form of the disease, which may develop in a second bone cancer called osteosarcoma. Also, they could pass the retinoblastoma to their children.

This cancer has been fascinating scientists for a long time. A Mayan stone bust dating from 2000 B.C. portrays the way the eye of a victim of advance retinoblastoma. The first clinical record of retinoblastoma was produced by a Dutch anatomist in 1597: “I opened the cranium of a three-year-old infant,” he wrote, “it had been suffering for some months with an enormous tumor of the left eye, such that the whole ocular globe with all the muscles made an outward projection, and this mass had increased in such proportions that the protuberance had the size of two fists.”

Drawing of a large retinoblastoma from 19th Century (Wikipedia)

The young patient died, as did every child with retinoblastoma for the next 250 years. Doctors tried to find out the cause of the disease, proposing everything from fungal infection to trauma to the eyeball to an excess of candlelight.

The inherited tragedies

In early 1800s, some surgeons decided to remove the eyes of patients in an attempt to save lives. It seemed extremely rational, however at that time this was a very grisly operation, since the anaesthesia hasn’t been invented yet. Even though the patients were willing to sacrifice their eyes, the treatment always failed, because doctors were not able to diagnose retinoblastoma until the cancer had spread to the optic nerve and even to the brain.

Ocular fundus aspect of retinoblastoma (Wikipedia)

In the mid-nineteenth century, two important medical tools, chloroform and the ophthalmoscope came to the world. With the ophthalmoscope, doctors may see small white patches on a child’s retina, which is an early sign of retinoblastoma. With chloroform, the young patients had their eyes removed in a less cruel way. Partly or completely blind, those children at least had the chance to survive to adulthood.

However, as the victims of retinoblastoma started to give birth to their own children, an astonishing pattern emerged: some of the victims would pass the retinoblastoma tragedies through the blood band. In 1866, a record showed that a man, who had had his right eye removed when he was a boy, fathered three children with the rare cancer. Over the next decades, people realized that perhaps there were two retinoblastomas: inherited and sporadic ones.

Although these two kinds of retinoblastoma seem identical, the course of the tumor is not. Sporadic retinoblastoma arises in older children (eighteen months or so), while inherited retinoblastoma finds victims about nine months old. Young patients with inherited retinoblastoma usually have more than one tumor in both eyes, while sporadic retinoblastoma patients have only one single tumor in one eye. In a word, the inherited form is the more aggressive of the two.

Two-hit hypothesis

In 1971, an American physician called Alfred Knudson formulated a bold hypothesis after analyzing the records of 48 retinoblastoma patients. He believed that cancer requires two mutations, that is, two “hits” to get started.

Alfred Knudson (BMJ)

Babies with inherited retinoblastoma receive one mutation from their parents, and as a result, all the cells in their bodies contain the first “hit”. However, they would not develop tumors until the second hit comes, which may be as simple as the errors in DNA replication that occasionally occur during cell division. In most people, such errors bring no harm; however, for the babies who were born with one retinoblastoma mutation, they can cause fetal cancer.

The two-hit hypothesis explains many of the mysteries about retinoblastoma. For those children with inherited retinoblastoma, they only underwent one random mutation; for those with sporadic retinoblastoma, they suffered from two random mutations – which would take longer time. It clarified why inherited tumors would happen at such a young age, and why they are more likely to produce several tumors.

Knudson’s hypothesis permanently changed the understanding of tumorigenesis. However, he didn’t even try to explain what the two mutations may be: “At that point there were no chromosomal data to go on, and you can only take theories so far without running into the realm of fantasy.”

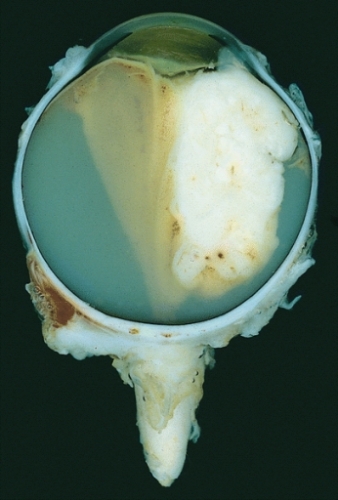

Large exophytic white tumor with foci of calcification producing total exudative retinal detachment (Wikipedia)

The discovery of tumor suppressive gene

The fantasy began to fade in a surprising speed. By 1980 geneticists had already been able to narrow the location of retinoblastoma gene to a specific portion of chromosome 13, a region called q14.

Scientists wanted to find out the retinoblastoma gene, which was extremely difficult. This small region encompasses five million base pairs of DNAs, whereas the average human gene is only about 20,000 base pairs long. Discoveries suggested that retinoblastoma gene was a “good” gene: rather than being switched on to cause cancer, it became malignant when turned off by mutations. We are talking about finding a tumor-suppressive gene that wasn’t doing anything in tumor cells, and that was doing something completely unknown in normal cells.

After years of hard work, scientists from Harvard Medical School identified retinoblastoma gene “RB” and when their report appeared in Nature on Oct. 16, 1986, it drew a globally enthusiastic response. There were stories even in TIME, the Wall Street Journal, and the New York Times. Later people discovered that RB protein is dysfunctional in several major cancers, so are some other tumor suppressive genes. They are an important part of the story of cancer, and someday people might be able to design a treatment by making a drug, that, instead of inhibiting the “bad” pathway, mimics what the “good” protein is doing.

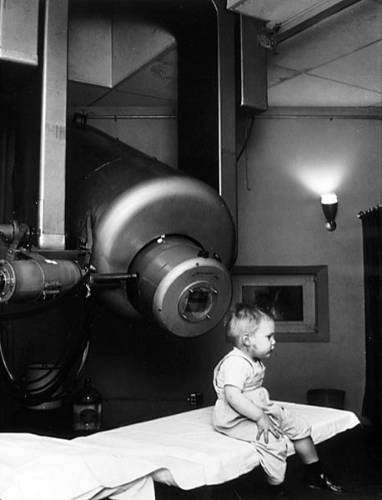

The first patient treated with the linear accelerator (external beam radiation therapy) for retinoblastoma, in 1957 (Wikipedia)

Chinse<<<

Recourses:

1. American Cancer Society (2003). "Chapter 85. Neoplasms of the Eye". Cancer Medicine. Hamilton, Ontario: BC Decker Inc. ISBN 978-1-55009-213-4.

2. Byrne, J., Fears, T. R., Whitney, C. and Parry, D. M. (1995), Survival after retinoblastoma: Long‐term consequences and family history of cancer. Med. Pediatr. Oncol., 24: 160-165.

3. Knudson, Alfred (April 1971). "Mutation and cancer: statistical study of retinoblastoma". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 68 (4): 820–3.

4. Friend, S., Bernards, R., Rogelj, S., et al (1986). A human DNA segment with properties of the gene that predisposes to retinoblastoma and osteosarcoma. Nature, 323, 643–646.